A century ago, this grand dinner celebrated the Philippines — without Filipino food

It was a marvelous dinner. One hundred guests, many of whom were senators or generals. An ornate banquet room in the Willard Hotel and floral arrangements of magnolias, dahlias and lilies of the valley. There was chicken Perigueux and potato Lorette, ham and an array of salads, and, for dessert, a peach mousse and petits fours. The date? Aug. 30, 1916.

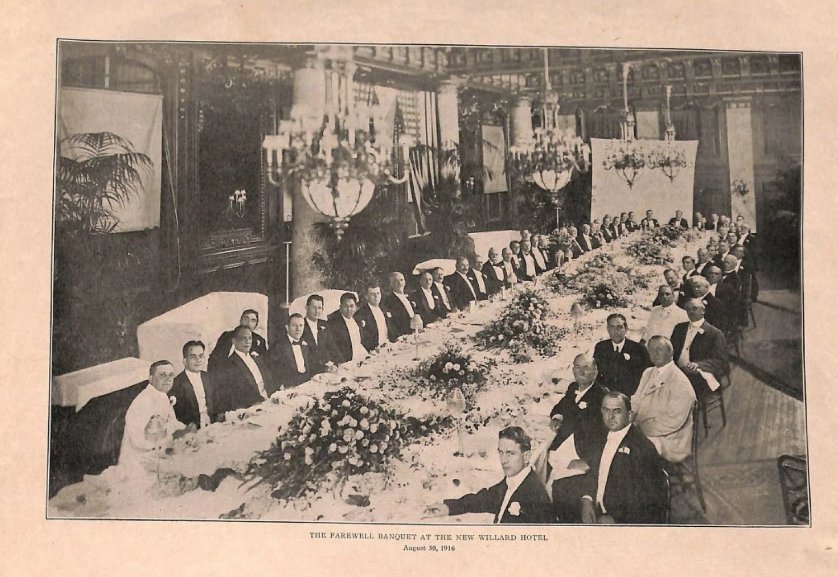

One hundred years ago, this grand party at the Willard was thrown by Manuel L. Quezon, the resident commissioner who represented the Philippines in the United States, which acquired the colony following the Spanish-American War. But the Jones Act of 1916, authored by Virginia congressman William Jones, established America’s commitment to the Philippines’ independence and structured its legislature. The bill had been signed that morning, and the next morning, Quezon would depart for Manila. The dinner was his farewell.

This photo of the banquet was published in “The Filipino People” (Courtesy of Philippines on the Potomac).

Researching the history of Filipinos in Washington is a hobby for Erwin Tiongson, a professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, and his wife, Titchie Carandang-Tiongson. It’s an effort “to make Filipino-American history a little bit more tangible and immediate to people who care about those things, including our two children,” Tiongson said.

They first learned of the dinner in a coffee-table book and then dug through old Filipino newsletters and magazines, encountering lengthy accounts of the dinner, recalling all of the speeches, the gifts, the aforementioned flower arrangements and the menu. Along with Hank Hendrickson, executive director of the US Philippines Society, they realized that they had enough information to reenact the dinner on its centennial. The menu, which was printed in French in the Philippine Review, was as follows:

This menu was originally published in the Philippine Review. White Rock is a brand of mineral water, says Titchie Carandang-Tiongson. (Courtesy of Philippines on the Potomac)

Reenacting the dinner is a more immersive way for the embassy’s guests — which will include Jones’s descendants — to experience the era they are celebrating.

“You’re getting a chance to experience living in it rather than reading about it,” said Bruce Reynolds, president of the Culinary Historians of Washington D.C. Dishes from 100 years ago weren’t radically different from what we eat now, though “cooking today, I’d say, has more layers of flavor.”

Joyce Javillonar, program manager for the US Philippines Society, said the reenactment “transports you to this time. We’ve said, ‘Come in 1916-era attire if you want to.’ I think there’s curiosity — what was it like?”

At first, the organizers went to the Willard to see if they could pull off a precise replica. But when the hotel priced it out, the cost was more than $250 a head, so they decided to host it at the embassy and enlist a caterer. Filipino chef Luis Florendo, whose family owned the former Sony’s Filipino restaurant in Baltimore, is overseeing the dinner, which will be hosted for a private group of about 30 people.

“It’s a very classic French menu,” said Florendo. “What struck me was that while it was very classic, it had touches of the very southern Washington culture, such as the pickled okra and the Smithfield ham.”

When Carandang-Tiongson had the menu translated, she was surprised by a few things, too. The descriptions of the dishes seemed fancy in French, “but it sounded more ordinary when it was translated in English.” Then she did some research: Celery was all the rage back then (radishes and olives, too). Still, “‘Okra served cold’ didn’t sound good to me,” Carandang-Tiongson said.

Of course, it would be difficult to replicate the menu exactly since the dishes have little description.

“There’s no one now who knows exactly how, for example, the chicken was actually prepared and served,” Hendrickson said. “I looked at it, and there’s several different ways to do the sauce,” which classically includes Madeira and black truffles.

Because their dinner will be smaller, they cut the sea bass from the menu. As well as one, um, side dish.

“We’re not offering cigarettes,” said Hendrickson.

There’s a certain irony to the timing of this feast. Filipino food is having a moment — it’s one of the trendiest cuisines in America this year, and D.C.’s own Bad Saint was named the second-best new restaurant in the country by Bon Appétit. But even though they’ll wait two hours in line for it now, the dignitaries of Washington wouldn’t have deigned to eat Filipino food 100 years ago. That means that this celebration of one of the landmark moments in the history of the Philippines will take place over a meal that is American and European.

And even though they’re playing it by the book for this meal, Florendo notes similarities between the two food cultures. Glazed ham, for example, is a Filipino dish, too. “With just a very little twist [the dinner] could be very Filipino,” he said.

Quezon threw the dinner for his colleagues, but it ended up being a celebration of his own career in American politics, which was successful in spite of great odds: He initially did not speak English. Congressmen once referred to Filipinos as “barbarians and half-emerged savages.” Quezon went on to become president of the Philippines from 1935 to 1944.

“We went to the Philippines not to establish tyranny, but to set wider the bounds of freedom,” Wisconsin Rep. Henry Cooper, one of the many guests who toasted Quezon, said to loud cheers that night. “We owe much to our host that we are succeeding in that great task.”

“Food cements relationships,” said Hendrickson. “The fact that the Philippines put on this very wonderful dinner for the members of the Congress validated in their minds that they were doing the right thing.”

from: washingtonpost.com